It’s always a great feeling when a writer blindsides you in the telling of a story. There you are, you’ve been taken in hand and gently guided into another world, and things are moving along and it all feels perfectly normal … basically, you’ve been quietly seduced, and you’re not even aware of it, until a scene arrives and in a flash, everything changes.

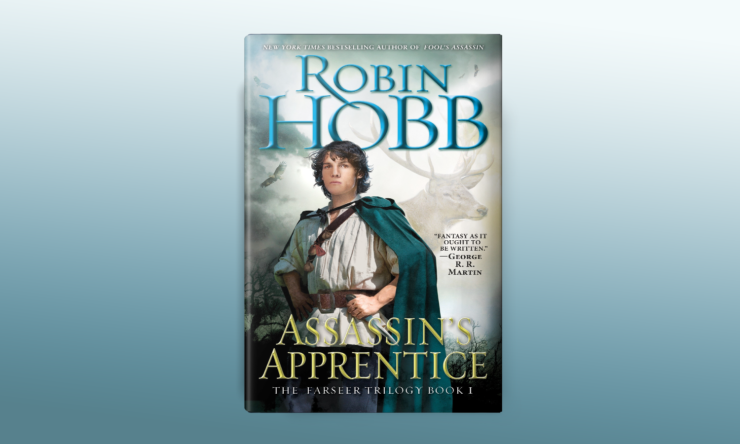

I’d not read Hobb before and knew nothing of her. I don’t know why I bought Assassin’s Apprentice; the impulse to buy is pernicious.

Started reading, admired the controlled point of view, the leisurely pace. Liked the boy-and-his-dog riff that was going on. Never even occurred to me that something was odd about that relationship, until the Scene. I won’t spoil it here, but that relationship ends with a brutal event, shocking in its seeming cruelty. Yet, it was in that moment that I realised the fullest extent of that quiet seduction. I’d bought so completely into the boy’s point of view that I sensed nothing awry about it.

Now, it takes a lot to surprise me when it comes to fiction. One of the curses to being a writer is how it affects one’s reading, and, often, how it can ruin all those seminal favorites one grew up with. Stories that sent your young imagination soaring now return as clunky writing, awkward scenes and purple passages rife with phrases to make you wince. The bones of construction are suddenly visible, for good or ill, each one now arriving as a lesson in how or how not to do things. It’s a humbling lesson in how nostalgia can only thrive inside a shell of frail memory, too fragile to withstand a closer look (also a lesson in how dangerous nostalgia can be, especially when applied to the real world).

Back to that scene, and everything that led up to it. I can’t be a lazy reader anymore. I don’t think many professional writers can. It’s hard these days to let a work unfetter my imagination. I’ve run the shell-game enough times myself to get taken in by all the old moves. That’s why, in retrospect, that passage left me stunned, rapidly flipping back through the pages that led up to that scene. Rereading (I almost never reread), and then, in wonder, deconstructing, line by line, to catch every subtle tell, every hint that I missed the first time around.

Robin, that was brilliantly done.

One of the earliest lessons I received as a beginning writer, was all about point of view (POV). My first story, in my first workshop, was lauded by the teacher for its tight control of POV. In proper workshops the author of a story has to stay quiet during the critique. Good thing, too, since I had no idea what POV was. Yet it turned out that I’d done a good job with it (whew). I felt like an imposter, undeserving of the praise given me. Fortunately, that writing program also had required electives in non-workshop creative writing, and the first class we all had to take was called Narrative Structure in Fiction, and that’s where I found out about POV, and exposition, setting, tone, atmosphere, diction level, dialogue and all the rest. They became the tools in the toolbox.

On one level, point of view can be straightforward and simple. You see the world through one character, see only what they see, experience only what they experience. Most stories these days use the third person limited omniscient POV, or first person. A story can contain lots of these third person limited omniscient POV’s, or just one. It’s flexible, allows for varying diction and tone (by tying the narrative style to the POV) and helps the writer limit the details seen at any one time.

But there’s another level, and it’s much more rare. I mention “seduction” earlier in this essay, and sure, all POV’s seduce in one way or another. But how often is that seduction deliberately, diabolically subversive? Or, rather, how often is that attempted and done really well? Technically, this goes to something called the “naïve narrator,” but there’s more to it than that. With each character’s POV, we are invited into their world-view. Because it often has familiar points of reference, we buy into it without much complaint (until and unless the character does something egregious, and if the POV is a child’s, that almost never happens, because we like to think of children as innocents).

It’s no accident the child POV is popular in fantasy fiction, as those “uneducated” eyes provide an easy vehicle to introduce to the reader the strangeness of the fantasy world and its goings on. Knowledge is fed piecemeal, at a child’s pace of comprehension (by extension, it’s also no surprise that the modern fantasy readership, having passed through that stage of “fantasy-reading-education,” has now grown past the trope).

So here I bought into Fitz’s little world, bought into its seeming normality, only to have it all suddenly torn away, and the child’s horror, bewilderment and grief was in an instant, mine as well.

To this day in the workshops I occasionally teach, I cite the opening chapters of Assassin’s Apprentice as required reading when it comes to point of view, and as a prime example of what it is capable of achieving, when handled with consummate control, precision and intent.

Mark Lawrence has since written a fairly subversive child POV, but that child is a sociopath, so the effect is not quite the same. We’re invited into a close relationship by that POV, and then asked to watch the boy setting fire to kittens (metaphorically), and then give him the high five. My point in this latter example? Only that subversion of point of view can go in any direction the writer chooses.

Robin Hobb taught me a helluva lot with Fitz. I’m pretty sure I told her this the one time we sat at a restaurant table in Seattle (along with a bunch of other writers), but she probably doesn’t remember and besides, I may have been drunk.

Originally published in April 2016.

Steven Erikson is an archaeologist and anthropologist and a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His New York Times bestselling Malazan Book of the Fallen has met with widespread acclaim and established him as a major voice in fantasy fiction—the latest installment, Fall of Light, is available now from Tor Books. He lives in Canada.